So many things, mostly simple and small; Yet all adding up to an experience quite special.

So many things, mostly simple and small; Yet all adding up to an experience quite special.

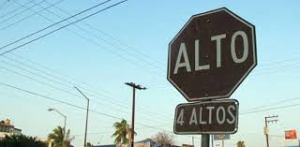

Driving: You see alot of “4 ALTO” while driving. They look familiar: Octogonal signs at intersections, red with white borders. They are not “Stop” signs, though. There are a number of stories of Grigos being pulled over for stopping completely at a “4 Altos”: dangerous – inviting a rear-end collision. Driving here is more organic, interactive – it flows. EVERYONE at an intersection knows exactly the order each vehicle arrived and that is the order (without exception!) that cars proceed.

The proper procedure is to slow enough to see who else is there: if no one, roll on thru at around 5 – 10 mph. If others are already present, slow down enough to give them their precedence, but try to keep rolling. If you’d like to see the “Mexican Stink Eye”, try going out of order at a “4 Altos”. The rebuke is not subtle. And, if you fail to proceed when it’s your turn, no one will wait for you although those going in your stead may hurl a friendly “Puta Madre'” (yeah, sound it out) in your direction

.

On the other hand, although I’ve driven here for several years now – it is very, very rare (much more so than in the US) to see dented cars or accidents. Everyone knows there’s alot of bad driving so they are more careful. As an example, I ride my bicycle as often- as I did in Oregon and Washington (two of the most bike friendly/aware states).

And, there have been far fewer “close calls” (swervers, potential “car dooring”, intersection roulette, etc) in Mexico. Partly, that is because the people are much more courteous. Here, pedestrians (and bicyclists) really DO have the right of way. There are ALOT of Policia on many street corners whose sole responsibility is to make sure that pedestrians crossing the street do so at their choice of time and place and without molestation. Of course, that does make driving more interesting because people are likely to “pop out” without alot of warning. So, here – people yield to people and not machines. It is charming to be at the curb and routinely have Mexican drivers in all lanes stop for you to cross.

And, there have been far fewer “close calls” (swervers, potential “car dooring”, intersection roulette, etc) in Mexico. Partly, that is because the people are much more courteous. Here, pedestrians (and bicyclists) really DO have the right of way. There are ALOT of Policia on many street corners whose sole responsibility is to make sure that pedestrians crossing the street do so at their choice of time and place and without molestation. Of course, that does make driving more interesting because people are likely to “pop out” without alot of warning. So, here – people yield to people and not machines. It is charming to be at the curb and routinely have Mexican drivers in all lanes stop for you to cross.

There is not a speeding problem in Mexican towns. No, they don’t have alot of chubby cops dressed as storm-troopers hiding with their little radar guns. There’s no $160.00 tickets for going 10 mph over, no judges to glower at you and your insurance premiums don’t go up if you speed.

That’s because of the practicality of Mexico. If they want you to slow down in a certain area, they lay down a BIG non-subtle speed bump (they are everywhere: some with signs and some not). You nail the same “tope'” at speed only once: the wheels leave the ground, your head hits the ceiling and contents go flying about. I figure the average suspension has a lifespan of about 75 -100 tope encounters.

That’s because of the practicality of Mexico. If they want you to slow down in a certain area, they lay down a BIG non-subtle speed bump (they are everywhere: some with signs and some not). You nail the same “tope'” at speed only once: the wheels leave the ground, your head hits the ceiling and contents go flying about. I figure the average suspension has a lifespan of about 75 -100 tope encounters.

And, although occasional encounters with polite and smiling “Policia Municipal” are common, I’ve never heard of anyone getting a ticket. No, rather than the $100 – 200.00 ticket you can expect to see from you local ill mannered, rude and abrupt US SS-cop, the pill here is far more palatable. It’s called “Mordida” or official bribe-taking and it is well understood, mostly accepted and practiced through-out government (espcecially by traffic cops dealing with Gringos). In such cases, there is a street theater that has certain moves. You are pulled over, usually, for “DWG” (Driving While Gringo: not unlike the numerous “Pretexts” offered by our home-grown officers). The initial move is the most importante’. If you are “stupido'” enough to furnish a real (ie “official”, stiff) US driver’s license your mordida just went up exponentially. That’s because you either pay the extravagant mordida demanded (2000 pesos – still, at an exchange rate of 14;1, it’s less than $200.00), or the cop just walks away with your license and you’re screwed when you get back to the states.

The necessary “gear” for a DWG traffic stop is a color laser-print (laminated) copy (ie fake and limp) of your ID, a camera(ie smart phone), a piece of paper & pen – and a two hundred peso note all in an envelope above your visor.

As the Policia officer approaches with his big smile, you smile back and hand him your copy of the license, pull the camera – point and click, while saying “Sonrisa” (ie “smile”). After the pleasantries where you confirm you’ve given him your only ID, he will list all of the many infractions and the horrific fines associated with them. You say nothing but continue to smile. If he becomes in any way gruff, you simply ask to be taken to the station to talk with the commandante. You also begin writing down his name, his car number, license number. A pal just told me of a beautiful move I’m really looking forward to: you act like your smart phone is on “record” while keeping him “in the picture” and asking “Por Que Halto y Que Quantos” (why stop me and how much?).

Once on level ground the friendly negotiations begin. He will start very high. You do not respond with a number, only a smiling/giggling “mas too mucho” and repeat the request to be taken to the station (which will eliminate his goal of pocket money and take alot of time). You can never be in a hurry during such negotiations. It’s best if they occur on a hot day while he is outside in the sun and your air-conditioning is keeping you cool. At some point he will ask you you if would prefer to resolve the matter informally, for less. THAT is where the negotiation really begins. You offer 50 pesos. He is insulted. He returns with 500 pesos and you’re aghast (have fun! “Por Favor – No Hable'”). The going rate (which everyone knows) is 200 pesos (or about $15.00). Once there, you are careful to not show any more money ( I have a special “mordida kit” containing only a single 200 peso note, pen and paper). You hand him the money, shake hands, and wish each other well.

You’ve made a new friend since he is happy and you’ve saved alot of money compared to a far less pleasant state-side encounter; and he can bring something special home to his ninos or his mistress. Mui Bueno.

It is fun to watch new or ignorant Gringos interact with locals, including store clerks. They will swagger up (like they do in the states), and abruptly demand what they want, in English – and either wait, pay too mucho, get inadequate cambio (change – which they rarely recognize) or learn that no such items are present.

That’s because the mode of interactions are reversed in Mexico. In the states, it is business before pleasure or pleasantries. You could go to the same US store for years and never know the clerks name, whether he is married or has ninos. In Mexico, things are more formalized and more personal.Things take more time. It is good.There is a necessity of greetings,”Hola…Hola – Buenos Dias/Tardis or Noches – Como Esta?…Bien, Gracias…Usted?….Bien, Bien, Gracias”, perhaps some discussion of the weather or family….No Rush…. Perhaps you ask his/her name and give them yours…Mucho Gusto! Only then, do you enquire (preferably in Spanish), “Do you have” (ie “Tiennes”)_____? They will now truly try to help you. If they don’t have it, they will tell you where to get it. And in any case, they are far more friendly and accommodating to Gringos speaking English than many of our Red-neck countrymen spewing, “Speak American or get out of the country”

That’s because the mode of interactions are reversed in Mexico. In the states, it is business before pleasure or pleasantries. You could go to the same US store for years and never know the clerks name, whether he is married or has ninos. In Mexico, things are more formalized and more personal.Things take more time. It is good.There is a necessity of greetings,”Hola…Hola – Buenos Dias/Tardis or Noches – Como Esta?…Bien, Gracias…Usted?….Bien, Bien, Gracias”, perhaps some discussion of the weather or family….No Rush…. Perhaps you ask his/her name and give them yours…Mucho Gusto! Only then, do you enquire (preferably in Spanish), “Do you have” (ie “Tiennes”)_____? They will now truly try to help you. If they don’t have it, they will tell you where to get it. And in any case, they are far more friendly and accommodating to Gringos speaking English than many of our Red-neck countrymen spewing, “Speak American or get out of the country”

You actually have encounters – rather than exchanges. And, of course – if one is too importante or busy for such things, the cultura will slow things down for them. It is the same when dealing with government officials. Be nice! You begin to feel far more connected and happy when this is practiced consistently. And, you will be greeted warmly wherever you go. You will know the names of the people around you and they will know yours – kinda like a Spanish “Cheers”.

If you care to become a permanent resident alien (easy to do), you will get very good health insurance for only a couple hundred dollars a year – and (yes!) a “Green Card”. This eliminates the need to leave the country every six months and raises your esteem with the locals who know you are trying to assimilate.

Cruisers (ie those of us that live on Boats) have an informal dress-code: Flip flops, shorts and Tees. ‘Pretty casual.If the shirt has a collar (even if dirty), we’re dressed up. And, of course, we think nothing of it. We even leave the docks and go into town like that. Until one befriends some locals and is informed – with great embarrassment to the teller – that cruisers are pitied because they dress so shabbily and smell bad. We have it so ingrained in our consciousness that we are the superior ones – living in a third world country with Third World people – that we fail to notice that most of the cars are as new (if smaller) than in the states; almost all (rather than a small majority) of cars are spotlessly clean.

‘Pretty casual.If the shirt has a collar (even if dirty), we’re dressed up. And, of course, we think nothing of it. We even leave the docks and go into town like that. Until one befriends some locals and is informed – with great embarrassment to the teller – that cruisers are pitied because they dress so shabbily and smell bad. We have it so ingrained in our consciousness that we are the superior ones – living in a third world country with Third World people – that we fail to notice that most of the cars are as new (if smaller) than in the states; almost all (rather than a small majority) of cars are spotlessly clean.

We don’t see that our hosts rarely wear tennis shoes or jeans, preferring nice leather shoes and slacks with nicer, newer and usually collared shirts; always clean.

Walk along most streets or malls in the US – how many people are smiling: not many; how many are alone: too many. In Mexico, there are more smiles, more laughter and joking – even among “open” strangers. Walk along a Malecon (Mexican boardwalk) and see all the families and friends holding hands or sitting on the benches, talking and smiling. One of the ways that Gringos are described is “frio” (cold). We’re not cold; we’ve been socialized by our culture to be tough and strong and afraid of strangers. That is why we are reserved in foreign cultures – especially given language difficulties. When this was pointed out to me, I began (for the first time in my life) to work on smiling more, joking more, initiating and continuing/expanding more conversations. I’m a terrible salsa dancer – but with this new attitude and the encouragement of my friends, I am beginning to learn how to dance “like no one is looking.” Such small things that make such big differences.

###################